Most timelines of the events that led to the November 9th resignation of former UM system president Tim Wolfe start at the 2015 homecoming parade, when the group Concerned Student 1950 stopped Wolfe’s car and recited a history of racism in Missouri and on the Mizzou campus. Wolfe was criticized for not speaking with the students, and many believe that perceived slight made Wolfe a target.

But to understand how Tim Wolfe, the president of the entire university system, became the target of this movement, we have to turn back the clock much further, to when Wolfe was first hired.

KBIA spoke to seven of the curators who played some role in the hiring process of Tim Wolfe: in the beginning, the end, or all the way through. From those conversations, a few common themes emerged. The first: it is impossible to talk about Tim Wolfe’s hiring without first mentioning his predecessor, Gary Forsee.

Listen

"Hiring a President" originally aired on February 16, 2016.

Click Here to Play

Laying the Foundation

“He was not your prototype of what historically had been viewed as president of a university system,” Don Downing, a former member of the University of Missouri System Board of Curators explained. “Gary came from a business background. He was CEO of Sprint.”

Before Gary Forsee became president of the university system, he was president and CEO of Sprint Nextel, and before that, he worked for BellSouth, a telecommunications corporation. In short, while he had a lot of experience, none of it was in higher education. And back in 2007, hiring a business person to run an academic institution was not as common of a practice, but some of the most pressing matters facing the university at the time of Forsee’s tenure were not inherently academic. Especially one: state funding.

Beginning in about 2002, state appropriations for the University of Missouri system began to dip. On just the Columbia campus, student enrollment grew by 45 percent between 2001 and 2012. In that same time period, state funding to the university dropped by 14 percent, from $193 million down to $166 million.

There are only a few ways to make up that difference in funding. Tuition is one of them.

“Tuition had gotten too high and we – at least I – wanted someone to monitor and make the university more efficient,” said David Wasinger, another former curator. “A lot of the administrators and a lot of the faculty have an insatiable appetite for spending.”

To the curators at the time, Gary Forsee’s business background made him sort of an ideal fit for the tough financial times facing the university system. Not everyone saw his hire in the same light, though, including Gary Ebersole, a University of Missouri Kansas City professor and member of the UM System’s intercampus faculty council.

“The hiring of Gary Forsee was a kind of out-of-the-box move by the board of trustees who decided they wanted a businessman. Faculty were not really involved not in the search itself and not enthused by the idea of a businessman.”

Forsee’s tenure was not without its hiccups, but over time he seemed to win over many stakeholders including the faculty. Even Ebersole agreed the arrangement seemed to work out, saying eventually, Forsee and the faculty “worked quite well together.”

In January of 2011, less than three years into his tenure, Forsee resigned following his wife’s cancer diagnosis. Downing says the perceived success of Forsee’s tenure opened the field of possibilities in the search for his successor, but it may have been more than just that. Although every curator we spoke to said they considered all types of candidates, by most accounts, given the continued financial constraints on the university system, most curators thought it made sense to replace Forsee with another person with a business background.

By this time, this type of hire with a business background seemed to be becoming popular nationally. Michael Bastedo is a professor at the University of Michigan specializing in higher education.

“It definitely seems to be more common that trustees are looking for a president with a business-type background,” he explained.

The complexity of running a university system isn’t always attractive to a business person, and even if it is, many of the most successful executives at large enterprises aren’t interested in making a move to the public sector.

However, just because curators decide they’re looking for someone with a business or political background to run an academic institution, doesn’t make it an easy task to accomplish. The complexity of running a university system isn’t always attractive to a business person, and even if it is, many of the most successful executives at large enterprises aren’t interested in making a move to the public sector.

The board hired Florida-based search firm Greenwood/Asher & Associates to track down a pool of candidates to replace Forsee, but by most accounts, the board wasn’t satisfied with the names they saw on the list. In response, the board also recruited candidates through other lines, like the business school alumni network - which is how Tim Wolfe’s name came to the applicant pool.

The curators courted Wolfe, trying to entice him to come back to his alma mater, and almost every curator we spoke with said they were consistently impressed by Wolfe’s temperament and personality.

“Tim Wolfe is an outstanding individual,” Craig Van Matre, who was involved in the hiring process, explained. “He has a very good personality, He is a good speaker, he is intelligent and quick, but he doesn’t have the kind of personality characteristics that are off-putting. He has two parents who were PhDs and professors at the university so he grew up with an academic background in effect in Columbia, Missouri.”

Wolfe got the job and things started okay. He was a good ‘ol boy who graduated from Mizzou. When the university came under scrutiny for their shortcomings related to Title IX issues, they were addressed quickly.

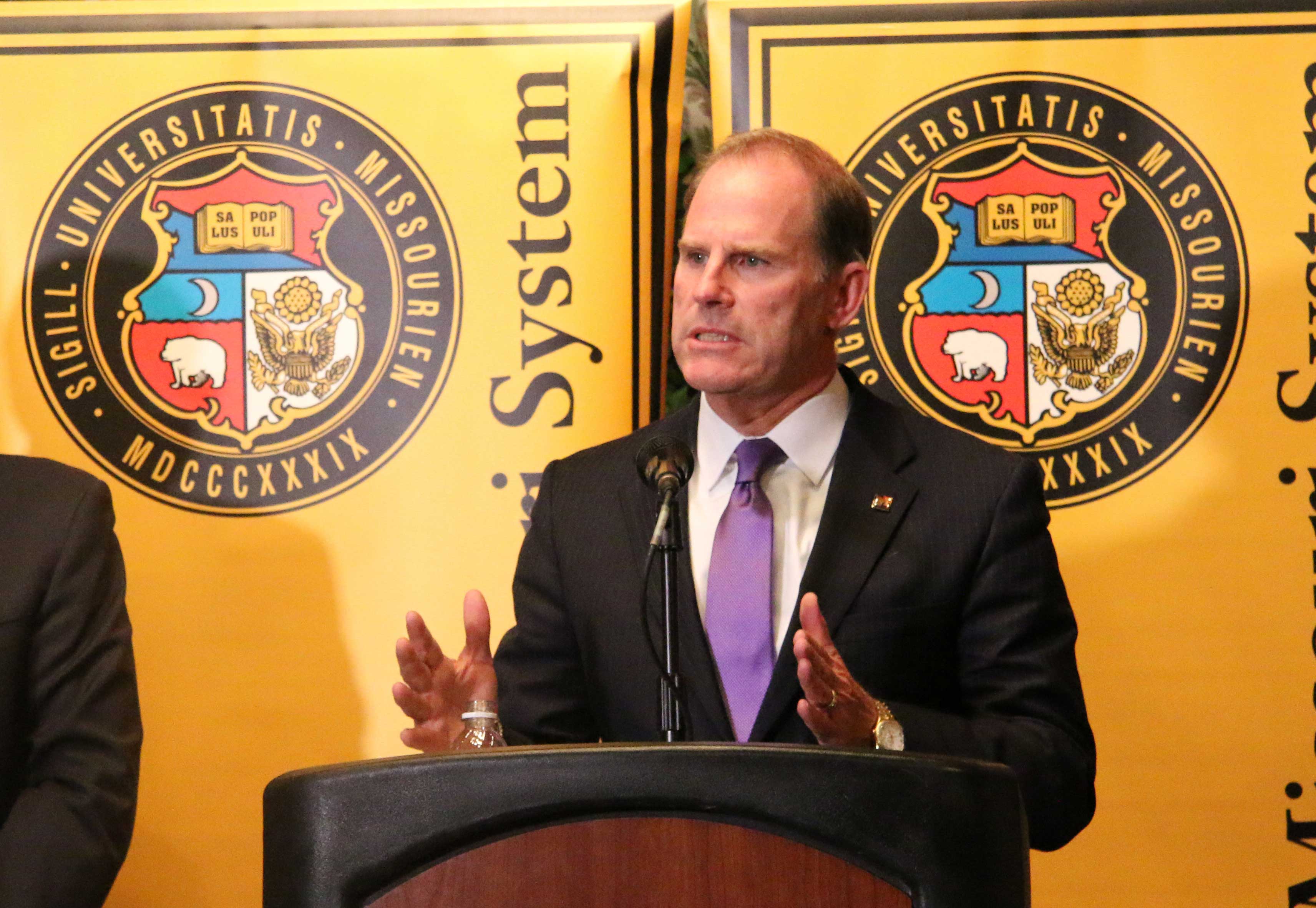

Former UM System President Gary Forsee speaking at a 2012 event.

KBIA / File PhotoTension Mounts

Then the tide began to shift after a few unpopular decisions and silence on a few major issues. Ebersole says Wolfe’s first misstep was in 2012, deciding to close the university-operated publishing house, the University of Missouri Press.

“He comes into the office, looks over budgets and sees that the university press was in the red,” he explained, “and he very quickly said ‘we’re not going to keep a university press that’s in the red’ without understanding that there is not a single university press in the country that makes money. In other words, universities subsidize the presses because it is an absolutely essential part of the investment in education that knowledge be distributed and disseminated to the world really.”

Ultimately Wolfe reversed this decision, but critics point to other decisions, too – like the expansion of sports facilities and overattentiveness to large donors at the expense of academic affairs, the institution’s bread and butter.

To many of the curators, Wolfe’s biggest misstep may have been the hiring of R. Bowen Loftin as chancellor of the flagship campus in 2013. Loftin, who previously was president at Texas A&M University, says he was hired by Wolfe to shake things up.

“The curators and president Wolfe both told me I was to be an agent of change.”

Loftin moved swiftly as chancellor. He held the position for not even two years, but in that time he rocked the Columbia campus boat. Under Loftin, 110 faculty members and 13 administrators accepted early retirement, reportedly saving the university millions of dollars.

“To be able to get about 10 percent of our senior tenured faculty to retire in one year, that’s an extraordinary thing,” he said. “To free up the resources required to renew our faculty in a very short period of time. that’s a very rare thing for a campus to be able to do so, I’m very proud this university was able to do that.”

But last year, when student aid and benefits ended up on the chopping block, things got sloppy. The University announced it would cut graduate student tuition waivers in half, then reversed the decision. Another snafu? Health insurance subsidies for graduate students were dropped with only a one day heads up – a decision Loftin himself eventually reversed. The damage was done, though. Large student demonstrations popped up on campus in response to these missteps, with many faculty members backing them.

This was the environment, even before Wolfe’s confrontation with Concerned Student 1950 at the homecoming parade: tension, not just about race, but about university funding and top-down decision making.

There were other high-profile decisions - cutting the vice chancellor for health affairs position, revoking hospital privileges for a planned parenthood doctor, even the resignation of the dean of the medical school was attributed to Loftin. All of these decisions drew backlash, from students, from faculty, even administrators - and most of it was directed at Loftin, but he claims in every case, he was consulting with Tim Wolfe.

“I shared with him everything I knew here on campus that I felt was relevant,” Loftin said, “and every major decision I made was discussed with him before I made it so we had a very strong relationship, I thought. Back in August of last year I had my second annual evaluation, in September, he sent me a letter giving me praise for my work and also indicating financial rewards along with that. So I felt - this was September of 2015 - I felt we were on good terms at that point.”

Wolfe did not respond to our multiple requests for an interview, but in a now infamous email published first by the Columbia Daily Tribune in January, Wolfe alluded to those decisions made by Loftin, adding that all of the deans on the Columbia campus had called for Loftin’s ouster and that Wolfe himself had requested support from the board of curators to fire Loftin.

This was the environment, even before Wolfe’s confrontation with Concerned Student 1950 at the homecoming parade: tension, not just about race, but about university funding and top-down decision making, all of it part of the struggle to move the university forward into the realities of the 21st century.

Former MU Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin announcing that he's stepping down on November 9, 2015.

Rebecca Smith / KBIAThe Breaking Point

Anger and tension brewed in the University of Missouri system. Many students were upset that administrators didn’t respond strongly when the student body President was called a racial slur off campus in September. Then, on Oct. 5, students in the Legion of Black Collegians were called the same slur on campus. Loftin released a video condemning the incident.

Emotions boiled over. It was just a few days later that Concerned Student 1950 stopped Tim Wolfe’s car at Homecoming.

The group issued a list of demands, and, since Wolfe was slow to acknowledge the racial issues even after the homecoming demonstration, one of the demands was for his removal as president.

Jonathan Butler, a black graduate student, began a hunger strike, saying it would only end when Wolfe was out as president. The football team backed the protesters, boycotting practice and games until Butler could eat again - when Wolfe was gone. Graduate students joined in. Faculty came out strongly in support of the protests, too.

On November 9, less than a week before the university would face a $1 million fine for not participating in a football game if the strike continued, the school reached its breaking point. Wolfe resigned minutes in to an emergency Board of Curators meeting. The protesters were ecstatic, but, as Craig Van Matre explains, the people who hired Wolfe were not.

“Wolfe did the only thing that he could do and resigned, then they had this symbolic head on this symbolic stick and not one thing of any practical value came out of it from there on. Very disappointing – very disappointing all the way around.”

For many of the curators who hired Wolfe, the issue of racism on the Mizzou campus was exactly that.

“That was a campus level issue, it should have been handled at the campus level,” Bradley explained, “and when it wasn’t handled at the campus level, I thought it was unfortunate that Tim fell on the sword for this issue.”

“Now,” David Wasinger said, “we have the remnants of a head football coach and some self-described radicals who have been running, or have the perception that they have been running, the University of Missouri, and you cannot have that.”

Former UM System President Timothy Wolfe delivers his resignation the morning of November 9, 2015.

Rebecca Smith / KBIARebuilding Relationships

Much like the decisions that rattled the Columbia campus in the past couple years - graduate student health subsidies, refer and follow privileges for the Planned Parenthood doctor, the dean of the school of medicine - the resignations of Wolfe and Loftin happened rapidly as well. The issue that escalated the unrest to a climax – which the board finally had to acknowledge – was a perceived indifference to racism on campus and the lack of action to combat it.

The fallout from that happened just as quickly.

In his confidential letter to friends that was later made public, Wolfe said he was concerned about campus safety and the escalation of protests turning into something historically embarrassing for the university.

Tom Hiles, the vice chancellor for Advancement, fielded a lot of concerns from alumni about the unrest. He reached out to Rod Kirsch, the senior vice president for Development and Alumni Relations at Penn State, who was on staff during the Jerry Sandusky debacle, if that tells you something about the magnitude and pace of the crisis. He was flown out to Columbia for a day. A crisis consultant was brought into the system for a week.

“When we’re in national headline coverage,” Hiles said, “we’re getting emails and calls – a lot of confusion, anger and frustration expressed.”

The marketing and communications department, headed by Interim Vice Chancellor Jennifer Hollingshead, put out a 10-point "State of Mizzou" article seemingly meant to salvage the school’s image. Then, university system officials, including Hiles and Hollingshead, held a conference call with Missouri alumni who were in the communications industry to hear their thoughts on the "State of Mizzou" article, a TV spot, editorials to newspapers, and the state of the university address. 1977 alumnus Ty Christian, who is black, was on the call. He says the alumni input seemed to fall on deaf ears.

“The first question we all asked in our own way was ‘Wow, okay. So I guess, not bad, but did you do any research? Did you talk to the key stakeholders, and then find out their perspective and their insight and find out how they felt?’ And, of course, the answer sort of kind of came back ‘No, we haven’t done it. This is what we think should go out,’ and I can say without hesitation you can hear the silence on the phone that the people who are in this profession and do it daily know that you don’t create any piece or material without talking to your key stakeholders and taking their temperatures.”

When Christian says stakeholders, he means alumni, students, donors, prospective students and parents. He says the literature put out by the marketing and communications department comes across as defensive with sections titled “It’s Not Just Mizzou,” “We Support Civil Liberties” and “Personnel Matters are Private.”

“If I’m a paying customer,” Christian said, “enough is enough – and listen, I’m not very happy with your service, you need to do something about it.”

Read More

Notes from the meeting of MU alumni gathered to discuss the university's communications strategy.

View on DocumentCloudIs School a Business?

Sara Goldrick Rab, a professor of educational policy studies at the University of Wisconsin Madison, says students have increasingly been viewed as consumers, hence why we are seeing more business managers as candidates to run schools – but it might not be that simple.

“Students are very much not consumers in the classic sense,” she said. “They are not purchasing something that is discreet and can be sort of bought and sold in an easy fashion. It means different things to different people, what education is, and it would kind of be like buying and selling love. It is not a tangible product and it again comes about in different ways for different people and means different things, but we all know it’s valuable.”

But on the other side, students today are also starting to understand they are an economic force – that if education is a business, they are vital to its viability.

“This means that this group of students is more likely to question the system to ask why things are happening, to object to the conditions of their lives. And so, I think the fact is that we’ve seen increases in enrollment among people whose parents didn’t go to college, among people from ethnic and racial minority groups and from people from low income families and it’s quite possible that adding them to the dynamic of a college campus helps to generate this change that we’re seeing today.”

The curators have to answer: How do you balance the economic needs of a university system with the academic and development needs of its students?

This will be an important issue on the table when the latest board of curators starts their hiring process for Wolfe’s replacement. The curators have to answer: How do you balance the economic needs of a university system with the academic and development needs of its students?

“It’s a brave new world,” Pamela Hendrickson, current chair of the board, said, “and President Middleton has brought to the fore how different the students’ experiences on campus today are from those we experienced when we went to college, and even from what my children experienced when they went through college. We need to be more attuned to that, and to the way students see the world.”

So far, the curators have spoken openly about considering academic candidates. They’ve also added student and faculty voting positions to the hiring committee, but this won’t simply solve the greater problems the system and Columbia campus face.

“This is a moment for Mizzou to be courageous,” Ty Christian said, “and by being courageous bold and innovative, without hesitation, we will be a leading university and a thought leader where people will be coming to us and saying hey how did you overcome those issues you had, because not only did you rebound, but you’re bigger better and bolder than you were before.”