Every year, around Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the city of Columbia holds an event it calls the “Columbia Values Diversity Celebration.”

There were more than a thousand people at the event this year from organizations throughout the city. Community leaders chatted with faith leaders from black churches, and leaders of other organizations. Kids were there on a field trip. Everyone was smiling.

Former University of Missouri Chancellor Brady Deaton was one of those smiling faces.

"Every year that I come there has been this very inspiring sense of togetherness and inclusiveness, we’re gonna tackle these issues together. I think that’s an earmark of the Columbia community, one of the highlights of the community. If we could bottle this and sell it, we would drive Columbia to the top of the heap, which is where I see it anyway,” Deaton said.

There’s music, an awards ceremony, all that. But when the keynote speaker took the stage, the tone of the event quickly changed.

Listen

"Starting the Conversation" originally aired on February 18, 2016.

Click Here to Play

Next Steps

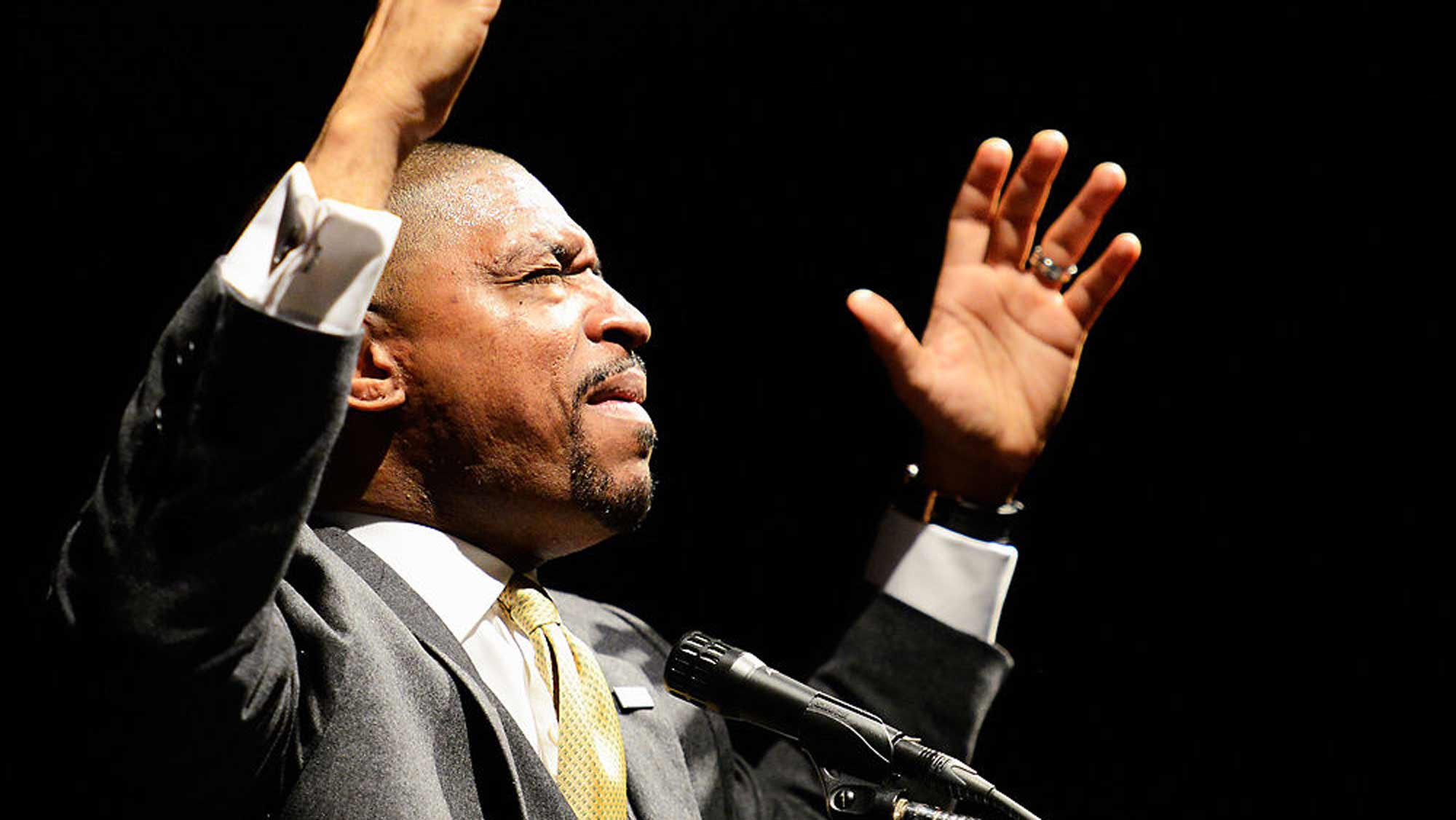

“Can I testify for a minute? I’m going to, you might as well give it to me,” Reverend Starsky Wilson said, to laughter. “Living in, and facing up to, the facts of Ferguson is enough to stress you out.”

Wilson is from St. Louis, and is a co-chair of the Ferguson Commission, which was created by Gov. Jay Nixon last year in the wake of the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri. He didn’t hesitate to connect the issues there to the issues here.

“We all live in Ferguson…when students have to risk their lives by standing in front of a car of one who is called to serve them when there has to be organized resistance…and risking of scholarship to lift the foot of oppression off the necks of those who pay taxes to support the institution that is there called to educate them: We all live in Ferguson,” Wilson said.

The Rev. Starsky Wilson speaks for the crowd at Columbia's annual Martin Luther King Jr. Day event.

Kayla Wolf / Columbia MissourianHe’s not speaking into a void: Twenty feet away is a table full of leaders from the University of Missouri – the interim system president, the provost, some vice chancellors and others. Wilson says Dr. Martin Luther King fought for equal access to opportunity in the 1950s and 60s, and then in the 1980s and ’90s the focus of these kinds of efforts moved to the issue of diversity.

“If diversity is about what you can see in the room, inclusion is about who actually gets to speak. Who got to set up the program? Who got to set up the agenda? Who gets listened to?” Wilson said.

Now, he says, the focus must be on inclusion and equity.

“Equity will have outcomes. I walk this progression from access to opportunity to diversity to inclusion, to equity because equity is required for reconciliation. We can’t have equal relationship as long as I’m a second class citizen. You want reconciliation? Let’s get some of this stuff right.”

The event ran longer than planned, and afterward many people stayed to visit. The MU leaders, though, headed straight for the door. They were late for meetings in Jefferson City, and back on campus. They have a lot of work to do.

One of them is Chuck Henson. As a black man, he says the progression Wilson spoke about rings true for him. Three of the four steps are right there in Henson’s title.

“Yes, that is the name of the division, division of inclusion, diversity, and equity. Vice Chancellor of inclusion, diversity and equity,” Henson said.

That Vice Chancellor position was created the same day System President Tim Wolfe and University of Missouri Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin resigned in November. Henson, an Associate Dean in the University of Missouri law school, was appointed to the new position on an interim basis the next day.

“We are at the point of talking about the truth. We are beginning that conversation,” Henson said.

In Each Other's Shoes

One of Henson’s first tasks was setting up new mandatory diversity training for staff and all incoming students.

Students start filing into an auditorium in one of the student centers for the third and final session. Students just needed to attend one. Since it’s the spring semester, it’s a smaller group: about 60 students. Many of them are transfer or international exchange students. It’s clear why the students are here.

Grant Durham is one of the students filing into the auditorium. He’s white, from suburban Kansas City. He shows up in a blue dress shirt with a matching blue bow tie.

"I think it’s important for students at the University of Missouri to have a good sense of home here,” he said. But he's not as convinced about what happened last term.

“I think, I’m not fully educated on the subject, but from what I’ve heard, I think it’s a little bit ridiculous that people threw such a fit about it."

Malcolm Edwards is another student here. He’s black, from the city of St. Louis. He wears a red hoodie and brown leather jacket. He sits down a couple rows behind Grant. I also grill him a bit about the session.

“Everybody has a different type of story. Something could happen to them. Something may not happen to them happens to other people, who knows?” Edwards said.

Both Durham and Edwards say they have friends of the opposite race, and have conversations about race with them.

“With someone who’s not of my race. It’s kinda, normally when you’re talking to someone of the same race I mean you don’t like say bad things about other people of other races but kind of in your head you know that just to watch out for that and not say something dumb. Even if it’s a joke, it’s not right to say that,” Durham said

“When I talk to somebody from a different race, they just don’t see it from like our point of view, I guess?… It’s just like they don’t see it, like understand it so. Cause you know they haven’t seen it and it doesn’t hurt them so I don’t want to say they don’t care, but they don’t care basically,” Edwards said.

It isn’t until I finish talking to them that I notice: Grant and Malcolm are both wearing the exact same brown boat shoes.

It isn’t until I finish talking to them that I notice: Grant and Malcolm are both wearing the exact same brown boat shoes.

This mandatory training has been branded as a ‘diversity orientation program.’ There are eight professors in the front of the room from all different disciplines. They’re of a variety of races and backgrounds.

They open with a loose discussion, and try their best to get students to engage.

Later, each of the professors gives a short presentation related to their field. Most of them have some relevance to the issues of diversity: one professor talks about people appropriating other cultures, like the example of a fraternity holding a Mexican-themed party where members showed up dressed like lawn care workers. One talks about his research into why Serena Williams makes far less money each year than Maria Sharapova, despite the fact that Williams, a black woman, is a consistently better tennis player to Sharapova, who is white. There’s even a section on comic books. Along the way, the professors all try to engage. Sometimes they get bites, other times it’s crickets.

“Building your own experiences with diversity means getting involved with student organizations, getting involved with service learning and study abroad opportunities and activities, but most of all, being willing to embrace the possibility to stretch yourself. That means putting yourself in situations that move you to think differently. To consider new ways of being. To grow and develop. That’s stretching,” Education Professor Antonio Castro said.

Toward the end, a few students share their stories: one about being biracial, but not looking it, another about what it was like to be friends with a gay student in a small town. After about two hours, it’s done.

Malcolm Edwards, the black student in boat shoes, was sitting right next to the door, and he’s the first student out. Grant Durham, the white student in boat shoes, walks out right behind Malcolm. Neither talk to any other students as they leave.

“I don’t think it will go anywhere from here. It’s just, you know, trying to get people to understand, I guess but, like, when you’re out in the real world, who knows what’s going to happen? So it may not be fixed but I mean who knows,” Edwards said.

There will be other discussions on campus focused on race this semester, but Grant says he’s not sure if he’ll have time for those:

“I’m pledging a fraternity right now, so I’m pretty busy with that and keeping up with schoolwork, but it’s a good program, and if I had the time and I was open then yeah, I would.”

Inspiring the Conversation

Stephanie Shonekan is the professor who ran the training. She’s a Professor of Ethnomusicology and Black Studies at MU. She was also recently appointed to the search committee for the new UM System President. She says training isn’t the way to think about what they’re trying to do with these sessions.

“We didn’t want to be teaching at them, we wanted them to know that this was to be a conversation so that in that conversation we can get to know each other. They can see that in classrooms there is conversation there is interaction and in a lot of ways we were trying to model what we do in class,” Shonekan said.

She says organizers purposefully chose the title, “Diversity at Mizzou: A Taste of Things to Come.”

“Our real hope is that they become intrigued… I keep using the word teased, you know, like we’re just teasing them and we want them to go out there and really explore,” Shonekan said.

But gow much does she think can we change?

“Tremendous. We all can. We all can. There is room for change on every level, from administration, to students to faculty to staff, we all don’t know everything, we’re all growing, and that’s what culture is, culture evolves and as a culture here at Mizzou, that’s evolving too, that’s a great thing,” Shonekan said.

The language is the same In the conversation in Chuck Henson’s new office in Jesse Hall.

“Culture doesn’t change, culture evolves…so it’s going to take quite some time for some of the things that we all desire to occur. But we’re getting started,” Henson said.

Henson knows his job is a tall order, and he’s still shaping it. It’s also only an interim post for him: three finalists are currently interviewing for the full time job. Henson says just in the last few weeks, student groups for Asian students, and Jewish students have reached out to him trying to figure out how they can utilize this new office. But, the events of last semester have created an urgent need to discuss the experience of black students on campus. Henson says, to find a way forward, he looked back to the list of demands Concerned Student 1950 made of administrators last semester.

“And I could see three areas. One: how do we treat each other? Two: what do we know? what are the facts? What should we know? And the third one was, who’s here?”

Henson is still in the process of navigating that relationship with Concerned Student 1950, recently writing the group to tell them, “If you sincerely want better relationships, the time for demands, threats and arbitrary deadlines is over — you don’t need them.”

One of the first concrete things Henson did was a work with the state historical society to create a 18-month lecture series on the black experience in Missouri. The first one was held in February, when a speaker spoke about the history of slavery in Missouri to a packed crowd in an auditorium on campus.

It’s not the first time administrators have tried this kind of thing–far from it. Some recent examples: The Chancellor’s Diversity Initiative was created in 2004 to try to address some of these same issues. It still exists, but now it will report to Henson’s office.

The university also created an initiative in 2011 called One Mizzou, following two high-profile racist incidents on campus in the two years prior. Then-chancellor Brady Deaton called One Mizzou his proudest achievement in office.

“One Mizzou was a statement by the students…They said we are one in our attempts to improve ourselves as a people, as a student body, as a community. And we will work together to achieve that. We are not going allow one incident or a little incident or another incident to break up the fundamental issues here that drive sort of the human spirit up and embrace the common efforts we have to build a better community,” Deaton said.

But the students who helped create it graduated, Deaton retired in 2013 and, by 2015, that initiative had completely dissolved–instead, One Mizzou was being used as a promotional slogan.

“Well, I think we learned that we have to maintain an ongoing dialogue about important issues. Staying engaged, demonstrating respect for all segments of the community, there is no alternative to that,” Deaton said.

Starting the Conversation

But there’s another big challenge here. Many students quite simply don’t know how to have these conversations in the first place, so they’re hesitant to engage.

Beyond the diversity training, there is a push to equip students to be prepared for these conversations. The Chancellor’s Diversity Initiative has been distributing literature with titles like “How to Talk about Race.” There are also diversity peer educators on campus. They meet with any group that will have them to go through exercises that help students explore these issues. Alanna Diggs is one of those educators.

“It’s really hard to come into a space for only an hour and to kind of drop a bomb on someone, like everything you’ve learned in society was maybe not what you thought it was,” Diggs said.

These peer educators run through exercises to try to get participants thinking about both racial and cultural differences.

“We read a series of statements and you take a step forward or backward depending on if the statement applies to you, for example, if you grew up with fifty books in your house, take a step forward. Those are the advantages that society might have given you and eventually you get to see the difference in where people are standing by the end of the facilitation and it’s a good way to use physical space to see how much of there are disadvantages and advantages in our society,” Diggs said.

Diversity Peer Educators have been on campus since 1997, but the group says it facilitated more discussions on campus last semester than ever before. Diggs says the past, it’s been a pretty unstructured program, but with increased demand, they’re starting to make things more formal, and adding new videos and exercises.

“Some of the things that make facilitating a little bit difficult are the people that don’t want to learn or the people that are just arguing, just to argue and that’s not conducive to a learning environment. But one of the things that I’ve learned from being a DPE is that it is very important to remember that all we can do as facilitators and all we can do as people that are trying to make change in our society is to plant a seed,” Diggs said.

Chuck Henson says this is where things get difficult, but it’s important to push through.

“I don’t anticipate any of the exchange to be counterproductive. At times one becomes impassioned because there are feelings involved, and everyone’s voice has a place,” Henson said.

"Who Gets Listened to?"

About three weeks after Chuck Henson and other University leaders sat and listened to Wilson, the UM Board of Curators held its next regular meeting. On the first day of the meeting, members of Concerned Student 1950 interrupted the meeting to re-read the list of demands the group made during demonstrations last semester.

Curator David Steelman responded by saying he didn’t consider it a disruption, and was glad to hear their voices.

Not everyone agreed with Steelman, though. The next week, State Representative Donna Lichtenegger, the chair of the House Appropriations-Higher Education Committee, announced they were moving forward with a plan to give every state college and University in the state a 2 percent increase in funding from last year, except for the University of Missouri system. She said it was in response to the events last semester, and because MU hasn’t fired Communications Professor Melissa Click yet for her actions during the student demonstrations. But Lichtenegger also said that for her, the last straw was when the Curators didn’t shut down the protest by 1950 at this meeting.

But back to that Curators meeting the week before. The day after the 1950 interruption, the Board opened its meeting in an unusual way.

“I believe that if we could all demonstrate respect for each other as a minimum and actually feel respect for each other as the ideal, issues of bias will be diminished,” Board Chair Pam Hendrickson said, making the introduction. “I am of the opinion that offense is taken when none is intended…. So how do we learn what other people find disrespectful and how do we communicate in a polite and respectful way that we feel disrespected by the words or actions of another? I’ve asked Chuck Henson, Chief Diversity Officer for the MU campus, to put together a panel discussion to address these questions and to open our eyes to making all of our interactions more positive.”

It was a four-person panel, two grad students, two undergraduates, three of them black, one white. They had an audience of the curators, interim system president, interim chancellor, and a variety of other leaders.

The students used some of their time to make suggestions.

“It would behoove the interim chancellor and the board of curators to immediately create a diversity task force, similar to the GSC task force that led to the immediate increase of graduate stipends. This research based action group will address the underrepresnetation of marginalized groups among faculty, graduate students and undergrads,” said student Timothy Love.

They also used some of their time to air grievances.

“So what does respect look like when it comes to the Board of Curators? Respect looks like not just have cisgendered majority faces sitting and staring back at me in shock that I’m saying all of this at 10:00 a.m. in the morning. That’s not respect. Respect isn’t having to go through Jeff City and understand that the real power isn’t here, but it’s in the supermajority that runs Jeff City,” another student, Kelcea Barnes, said.

“As long as the Board of Curators prioritizes profits and wealth over and above academics, there can never be a culture of respect. As long as students are viewed as commodities or sources of revenue, serious measures to solidify unity will never be taken,” Love said.

Ultimately, these students were given time that students haven’t had with this audience in the past to discuss these kinds of issues.

"For a long time we all kept silent. And we’ve gotten to the point now where we need you to listen."

“It’s not something that just all of a sudden happened, which I think that a lot of people thought. Because for a long time we all kept silent. And we’ve gotten to the point now where we need you to listen. And I’m happy that we’re here to have this conversation and dialogue and that we can move on from here and continue to have this conversation. Let’s not make this a thing that just happened now, and a few months down the road let’s revisit what happened,” student Jasmine Morgan said.

After about a half hour of statements, the curators asked some questions. There was some back and forth about the way diversity courses should be handled, and about the board’s action so far and the way forward. In the end, curators and the students found common ground.

“What I hear you all saying is that process is important, but when process gets in the way of action we either need to work on that process, or we need to what it takes to get the action,” Curator Steelman said.

"That’s a very good way of putting it, 'when process gets in the way of action,' I love that,” Love said.

Henson says steps like these are important, and appropriate.

“And it’s a different thing than what I think some have viewed as the students running the university. The students aren’t running the university, we are addressing their concerns. And that’s what ought to be expected of us, I think,” Henson said.

Of course, there are many other efforts too. Interim system President Mike Middleton says there will be money diverted to efforts to hire more black faculty members. Henson will set up new weekly meetings with student leaders.There are some other big efforts, and departments across campus are initiating their own, smaller efforts toward creating dialogue. And while this is often difficult, and sometimes controversial, Henson believes it’s the way forward.

“I haven’t yet heard anyone say I don’t want to become a better community, I don’t want to become a more respectful community. I don’t want to become a more diverse community, I don’t want a more inclusive community. So I take from that void of denial a message,” Henson said.

Special thanks to Rodney Davis, Ryan Levi, and Emerald O’Brien for their production assistance.