In August 2014, Ferguson, Missouri found itself at the center of a national debate about race, after white police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed African American teenager Michael Brown. Less than a year and half later, that focus shifted about two hours west. Once again, Missouri took center stage - this time at the state university's flagship campus.

But why Missouri? Missouri is not the biggest, or most populous, or the richest or the poorest state. As an entire state, it's neither the most urban nor the most rural, nor the least or most racially or ethnically diverse. Likewise, the University of Missouri is none of these things. But if you spend much time looking into the history of Missouri, and of the university, you'll find they both were forged in the fires of a nation deeply divided over race. With its geographic position between North and South, East and West, Missouri stands at a crossroads of policy, migration and culture.

Listen

"Past and Present" originally aired on February 15, 2016.

Click Here to Play

Missouri, MU and Slavery

The Territory of Missouri’s journey to statehood was fraught with debate over the issue of slavery. The abolition movement was beginning in the north, and some northern congressman didn’t want to see slavery’s reach grown. “For some of them, it was for humanitarian reasons, but for a lot of them it was really for political reasons,” said historian and UMKC professor Diane Mutti-Burke. “They were concerned about the growing power of politicians from the slave states. They didn’t want to see another slave state enter the union – because of that and so they fought quite hard about it.”

To preserve the balance, Congress came to the Missouri Compromise in 1820. Missouri joined the nation as a slave state, Maine as a free state, and the Missouri Compromise determined whether all other new states would be slave or free based on their location on the map.

Nineteen years later, the University of Missouri was founded, and the first leaders of the school didn’t escape the debate over slavery.

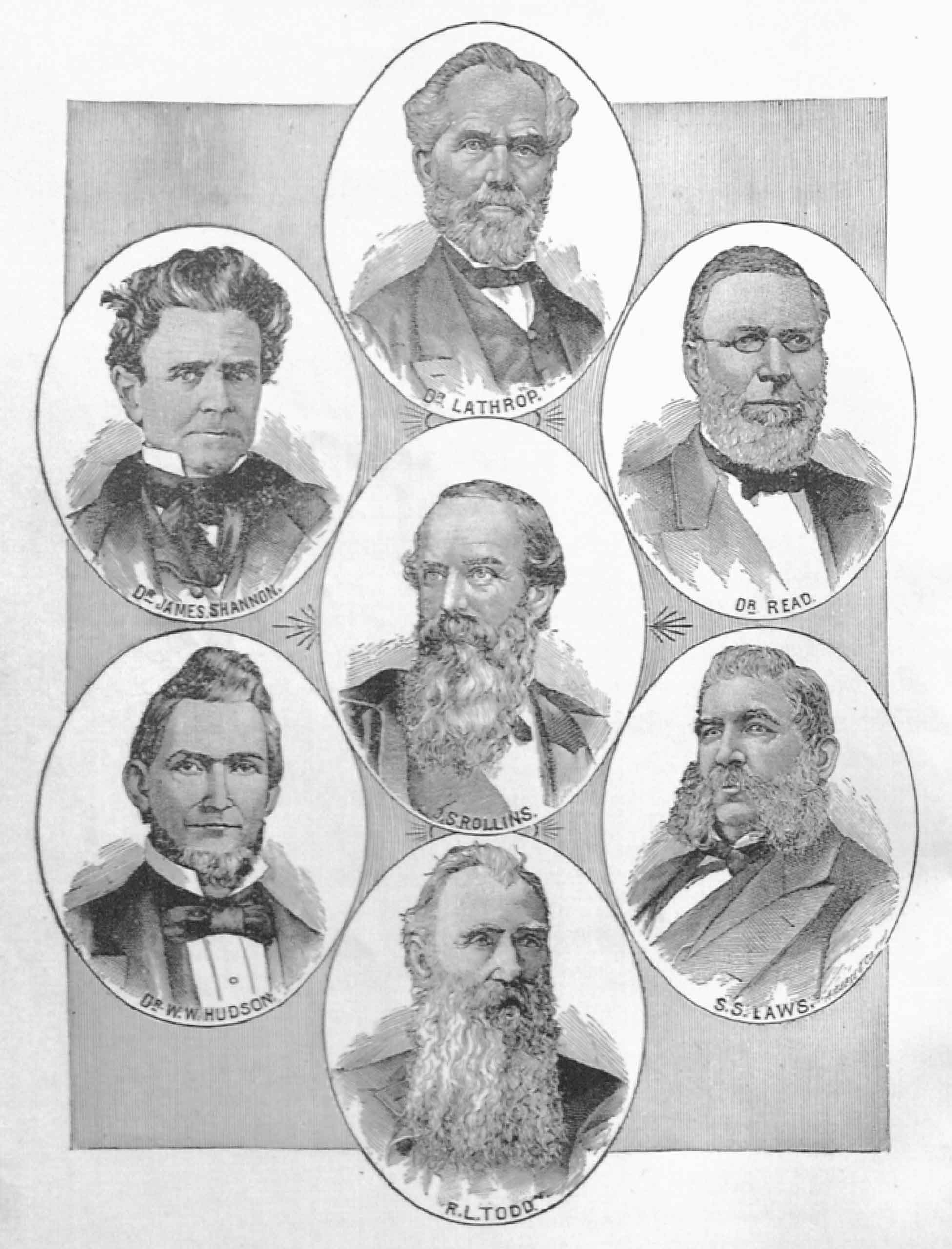

John Lathrop, A Yale-educated New Yorker, was the first president of the University of Missouri.

“He was teaching the sorts of things that might encourage students to be anti-slavery,” said Joan Stack , curator of art collections for the State Historical Society of Missouri. The little card hanging next to Lathrop’s portrait in the Historical Society’s gallery reads: “Although Lathrop was not outspokenly political, he was suspected of holding anti-slavery views.” Those suspicions may have fueled tensions between Lathrop and some members of the Board of Curators that ended with Lathrop moving north to become the first Chancellor at the University of Wisconsin. He was replaced by James Shannon, an outspoken supporter of slavery who made his views very clear. It was a position that contributed to tension with the legislature and to Shannon also leaving the university.

It is clear that some early university leaders owned slaves. James Sidney Rollins, a lawyer, politician and slaveholder, is often called the father of MU, in part because he helped raise the funds to establish the campus in Columbia. He was in Congress during the Civil War, and had originally voted against the 13th Amendment, which would abolish slavery, but later, Missouri abolished slavery at the state level. A few days after, Rollins gave a rousing speech in support of the 13th Amendment.

It’s a long speech, and in it Rollins wrote things that at times seem to contradict each other. He wrote that he would either support or abolish slavery - whichever maintained national unity, which was his most important goal. He wrote that although slavery was wrong, he believed it ultimately helped people. And he said he was “an anti-slavery man in sentiment, and yet, heretofore a large owner of slaves myself.”

He also wrote that “the institution of African slavery” could not be defended either upon religious or moral grounds, and said, “I am no longer the owner of a slave, and I thank God for it.”

An early issue of the University of Missouri's yearbook shows a selection of the school's first presidents.

University of Missouri / Photo CourtesySegregation and School

After the civil war, the formerly enslaved people of Missouri were free, but not equal. The state constitution called for segregated education, which meant black students could not attend MU - but the state still had to offer them higher education. So what is now Lincoln University was established in 1866 in Jefferson City for African Americans, but it didn’t offer the same courses as MU.

Gary Kremer is director of the State Historical Society of Missouri.

“If an African American student aspired to study or take a course of instruction that was not available at Lincoln, the procedure was that they would apply to the University of Missouri, be rejected, and then take their rejection to the legislatures so that money could be appropriated to send them out of the state,” he said. “Of course, it was Lloyd Gaines who challenged that system.”

Lloyd Gaines went to Lincoln University, but didn’t want to be sent out of state to attend law school. He wanted to go to MU, and he began a lawsuit in 1938 for admission. At that time, there were no black students at the university, and a black man had been lynched by a mob in Columbia just 15 years before.

The Supreme Court ruled that Missouri had to either admit Gaines to MU or create a separate law school for African Americans. The University chose to create a new law school, and Gaines seemed poised to continue fighting on the grounds that the new school was not equal. But his fight never reached a conclusion. Gaines was last seen in Chicago in 1939. He disappeared, and it’s unknown what happened to him. Legal scholars say his case laid the groundwork for the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954.

The same year Gaines disappeared, a woman applied to the MU school of journalism.

“The issue with Lucile Bluford was that she applied for admittance to the Missouri Journalism master’s program and they did not know she was black until she showed up on campus to register for classes,” said MU Journalism professor and historian Earnest Perry. “Once they realized that she was black they basically said ‘No, we’re not going to allow you to register for classes, your admission is rescinded.’ And then she took that case, or she and the NAACP, took that case to court.”

This had the same result as Gaines’ case: The state created a separate journalism school at Lincoln University rather than let Bluford into MU. But Perry says that while MU administration seemed immovably opposed to admitting African American students, polls by the student newspaper revealed a different attitude in the student body.

“Students overwhelmingly supported African American students being admitted to the University,” Perry said “The University officials, they acknowledged that the students wanted that but they were not going to change their policy.”

Lucille Bluford’s case was never fully decided. But finally, in 1950, the first African American students at MU began classes. That was 66 years ago.

Generations of Activism

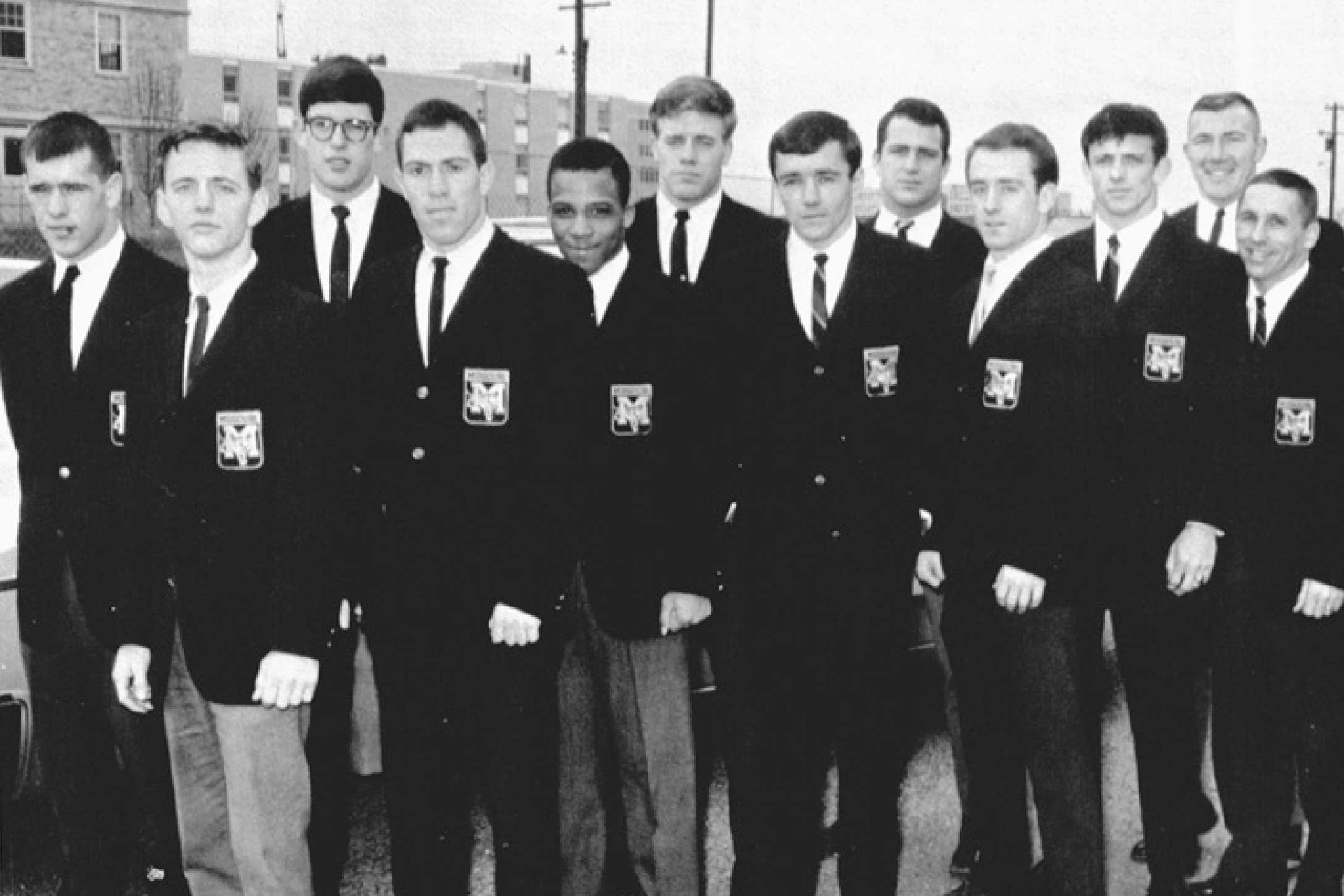

In the fall of 1950, the University of Missouri accepted its first nine black students, and for a while it seemed the University was making progress - sports teams were becoming integrated, black students were taking part in more student organizations and black sororities and fraternities starting organizing. However, throughout the 1960s, there were still just a couple hundred black students at MU, and racial issues remained a problem on campus. Discriminatory housing policies remained in effect until 1964 for on-campus housing and 1965 for off-campus.

One issue cited by a number of black students who attended MU in the 1960s was the performance of the song "Dixie" at university football games. While the song, which idealizes the slaveholding South, was being played, some students would wave confederate flags. During one game in 1967, black students waved a plain black flag in response, and a student had a gun pulled on him by a Boone County deputy sheriff.

The first black faculty member wouldn't even be hired until 1969.

In response to these incidents, a group of black students came together. According to a book compiled by the university's black alumni association in 1994, it was 19-year-old-sophomore Howard Taylor who then spoke up at a 1968 black fraternity meeting, saying "We need a legion of Black Collegians."

Howard attended MU in the 1960s and graduated in 1969. He's now retired in Jacksonville, Florida, and has a lot to say about his days at MU and his experiences as the vice-president of the Legion of Black Collegians or LBC.

"Being a black Mizzou student, our interest was how we look at our environment...and what can we do to change it in a peaceful manner. And that's what the Legion of Black Collegians is about - the peaceful approach, rather than the destructive or the really antagonistic approach," Taylor said.

He, along with his fellow Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity brothers, founded the Legion of Black Collegians in 1968, but they weren't officially recognized by the University for several years.

He said he turned on the TV last November and saw Mizzou was making the news again for many of the same issues he and other black students were dealing with in the late 1960s. He also said the early LBC presented MU administration with a list of demands in 1969.

"[The issues included] a lack of representation on the administration. The lack of instructors, professors that were minorities. The lack of coursework that was minority oriented, as well as the lack of accessibility to some of the university facilities without being harassed because we were minorities on campus."

46 years later, Concerned Student 1950 presented university leadership with their own list of demands. Some were identical to those from 1969.

Forty-six years later, black student organization Concerned Student 1950 presented university leadership with their own list of demands, some of which were identical to those given in 1969.

Concerned Student 1950 was not the first student protest movement since Taylor's days in the LBC. In fact, it was far from it. The University of Missouri has a long history of student-led protest movements. Race-related protests continued throughout the 1970s and 1980s. There was a South African divestment movement in the late 1980s where MU students built a shanty town on the Francis Quadrangle. The group MU 4 Mike Brown was created in 2014 following the shooting death of Ferguson teenager Michael Brown at the hands of police, and earlier last year, protests emerged over the school's treatment of graduate students and revocation of the hospital privileges for the local Planned Parenthood clinician.

Earnest Perry, an MU Journalism Professor and Historian, says all of these movements are connected.

"What we call the social justice movement today was the civil rights movement in the '50s, '60s and '70s. What was the civil rights movements of the '50s, '60s and '70s was what we called race issues or race matters in the 1920s and 1930s," Perry said. "So the names are different as you move through time, but many of the issues are the same and it all centers around equality."

Perry added that while some contemporary students complained that nothing has changed at MU since the 1960s, this isn't quite true.

"There were changes. You could see increases in the number of students in color on campus, you had the hiring of some faculty of color, [but] not as many as were demanded."

Taylor said it was disappointing for him to see that Concerned Student 1950 was fighting for many of the same things that he was fighting for back in the '60s.

"It's discouraging to me that it has been non-existent or so slow to change. Or it has changed and regressed in some cases because there was not a focus on it," Taylor said.

Marshall Allen, one of the original 11 members of Concerned Student 1950 said it's actually this lack of change at MU that inspires him and others to keep pushing.

"I'm in total agreeance that it is discouraging at times to see that," Allen said. "But at the same time it is also fuel for us. To make sure that we understand that we have to keep doing what we're doing if we want to effect substantial change in the long run."

Marshall Allen speaks to a crowd of press and onlookers at the protests on November 9, 2015.

Tyler Adkisson / KBIAAllen said that Concerned Student 1950 came together following a series of racially-charged events on campus last year, and following what he described as a lackluster response to those events by the university's administration. He added that Concerned Student 1950 chose to focus on former UM System President Tim Wolfe because he was at the top of an organization that "can remain negligent about the problems of students."

"We knew we had to make a head change," Allen said, "And we figured that getting him out or making sure that we got him to resign was one of the first steps in making sure that we had change. Because if the change starts at the top than the bottom has to follow.

Historian Sekou Franklin said the immediacy with which Concerned Student 1950 got Wolfe to resign and MU Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin to step down was different from many protest movements that had come before them.

"What they accomplished was a big deal," Franklin said. "Because it's often a case that as a response of the protest, universities would change leadership, but not so quickly. It may take a few years, or the person in power may plan to leave a year earlier."

Franklin, who wrote the book "After the Rebellion: Black Youth, Social Movement Activism, and the Post-Civil Rights Generation" on the topic of black student activism, said the most striking thing about the protests in November 2015 was the involvement of the university football team.

"The young people have a lot of influence and power, and particularly the athletes," Franklin said. "I can tell you a lot of universities are nervous."

Howard said he intends to continue to follow the events and student protesters at MU - in hopes that real change occurs in the future.

"They're changing themselves as well as the University for the betterment of those who come," Taylor said, "and I'm glad I participated in some change in the '60s so that Marshall, for whatever it's worth, he's there [at MU]. And when he leaves, he's going to leave it to somebody else, so in another 50 years we won't be talking about the same thing."